Decades Together

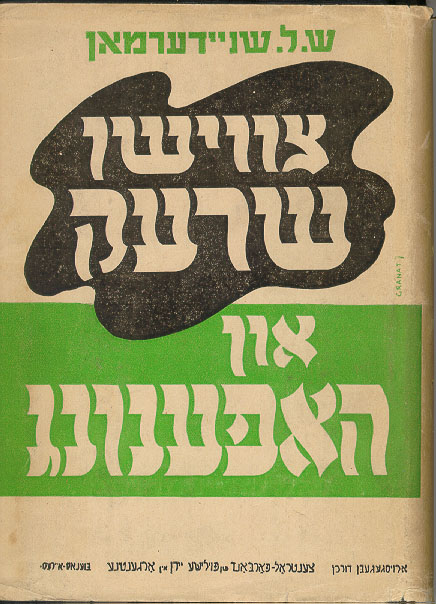

By Eileen (Hala) Szymin-Shneiderman

<p>translated by Fannie Peczenik from “What Time is it On the Jewish Clock”</p>

<p>September 14, 2000</p>

<p>Forlorn and grief-stricken in the painful weeks and months after the death of my husband, S. L. Shneiderman, I feverishly began to organize the stacks of papers that had accumulated in our little apartment in Ramat Aviv. I had a strong desire to hold on to the past, which meant tracing Shneiderman’s literary career step-by-step.</p>

<p>Even in the last few days of his life, he continued to devour the newspapers and magazines (in Hebrew, Yiddish, English, or other languages) that were delivered by mail or bought each day at neighborhood kiosks. He still read, cut out clippings, took notes (writing by himself or dictating to me) for future articles, although it was already clear he would never live to write them.</p>

<p>Through the long decades we worked together, it was my responsibility to save and file his published works, news stories and longer essays, only a fraction of which ever appeared in book form.</p>

<p>Throughout most of the tragic twentieth century, our lives were busy and bustling and, often, before we had time to finish with a current topic, something new occurred in the Jewish world or an international cultural event fired Shneiderman’s creative imagination. And so we were always on the run, hurrying to be on the scene wherever the news was happening.</p>

<p>We would come back from every trip carrying bundles of notes, books, and magazines that Shneiderman’s lively, evocative prose style would transform into compelling articles on contemporary events seen both from a Jewish perspective and from that of the world at large.</p>

<p>Writing did not come as easily to Shneiderman as readers of his often breathtaking descriptions might think. He showed no mercy to his own manuscripts; whole pages were frequently consigned to the waste paper basket. If he only rejected half a page, then a pair of scissors and paste were deployed. Unfortunately, I learned to use a word processor too late.</p>

<p>Shneiderman worked best under pressure. For a journalist this means at the eleventh hour — while the typesetter was waiting for the manuscript or a telegram with the latest news report was on the way. Even when the <em>Forwerts</em> became a weekly, the editors still had to wait until the very last minute for Shneiderman’s articles.</p>

<p>After I arrived in New York in 1940, I took a course in Yiddish stenography given by the Workmen’s Circle; the stenographer’s notebook served us both well.</p>

<p>When he was preparing one of his longer pieces of reportage, Shneiderman would often spend days searching for the first sentence. He didn’t believe in preambles: the first paragraph presented the reader with a concrete fact pointing to the subject under discussion. Not until later in the article did he permit himself to import memories, comparisons, and anecdotes. One sentence led to another and it was impossible to know how the article would end.</p>

<p>As his research and interviews show, Shneiderman was particularly interested in the problem of Jewish assimilation, conversion to Christianity, and the return to Judaism. This was not a new phenomenon in Jewish history because during the centuries of Diaspora, foreign influences were unavoidable and, in fact, often enriched Jewish culture, as it created new links in the golden chain of deeply rooted values and traditions.</p>

<p>In <em>When the Vistula Spoke Yiddish</em>, Shneiderman addressed the problem of assimilation through the story of the nineteenth-century Jew from Kuzmir, Itzchak Hoga. And in <em>Ilya Ehrenburg</em>, Shneiderman described the threefold division of that great writer’s identity: Jew, Russian writer, and man of Western European culture. Shneiderman again analyzed the same problem in essays on Heinrich Heine and, especially, Julian Tuwim. A Jew from Lodz, Tuwim was the most prominent Polish poet of the twentieth century; Shneiderman admired his work, wrote a great deal about him, and translated some of his poems. Contemplating these Jews estranged from their tradition, Shneiderman searched their works for that quintessence of Jewish identity, <em>dos pintele yid</em>, which usually surfaces at critical moments in history.</p>

<p>At the end, when Shneiderman could no longer travel far, his friends and colleagues asked him why he didn’t write a memoir. His answer was that his books and articles contained enough of his reminiscences and experiences, but the stimulus for recounting them had always come from contemporary events.</p>

<p>Nevertheless, among the papers on his desk, I found a substantial manuscript entitled, “My Beginnings as a Yiddish Writer — notes for an autobiography.” As I remember, these were the notes for a talk he gave in Canada. He always prepared himself well for his lectures, so these notes can be regarded as his memoir.</p>

<p>The manuscript begins with these words: “To retrace the steps in my career as a Yiddish writer — to return to the beginning — would be no small task. It would mean going back to the origins of modern Yiddish literature, as well as to Jewish political and social life in the reborn Polish republic.”</p>

<p>In these memoirs, Shneiderman talks about his <em>shtetl,</em> Kazimierz on the Wistula (or Kuzmir, as it was known in Yiddish); his family; his love for nature and for the life of the Polish peasants.</p>

<p>That was a time when, in Poland as elsewhere, artists and writers extolled village life. In 1924, the Polish writer, W. Reymont, was awarded the Nobel prize for his novel, <em>The Peasants</em>., which appeared in an excellent Yiddish translation by Schlomo Rosenberg, a close friend of Shneiderman’s. Incidentally, Rosenberg later became well-known for his Yiddish historical novels; he was also Sholem Asch’s secretary for fifteen years. It is worth noting that Sholem Asch himself was a candidate for the Nobel prize for <em>A Shtetl</em>, which, in its use of the rich, idiomatic language studied by Polish enthnographers and students of folklore, can be seen as the Yiddish answer to Reymont’s novel.</p>

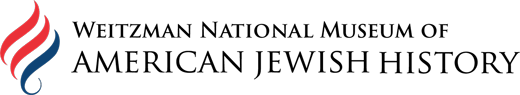

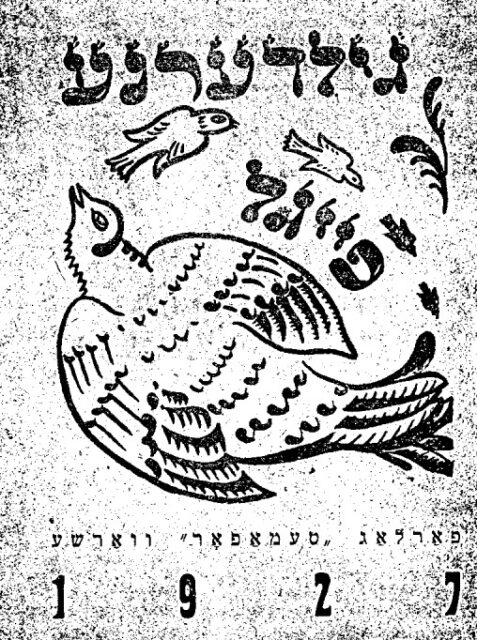

<p>The same kind of admiration for Polish village life is found in Shneiderman’s first book of poems, <em>Gilderne Feigl (Gilded Birds)</em>, which was published in 1927, two years after he arrived in Warsaw. His second volume of poetry, <em>Feiern in Shtot (Unrest in Town</em>), which appeared in 1932, depicts the author’s youthful experiences when, like most young Yiddish writers, he came to the big city from his small home town. The poems here are imbued with contemporary social issues — poverty, unemployment, rapid industrial expansion, rejection of war and militarism — as well as lyrical longings for his hometown. Some of the poems were published in the leading Yiddish weekly in Warsaw, <em>Literarische Bletter (Literary Pages)</em>, edited by Nachman Mayzel.</p>

<p>The poems Shneiderman wrote in the first few years after he came to New York in 1940, are much better known. By then the Nazis had already inflicted their savagery on Poland and we were overcome with anxiety about the fate of the Jews, especially our own family and countless friends. That cycle of songs, which was to be called, <em>The Hudson is My Witness</em>, was never published in book form, and only a few of the poems appeared in newspapers.</p>

<p>In 1925, when Shneiderman came to Warsaw from Kuzmir and wrote poems about poverty and the revolutionary ferment that dominated the Polish capital, he was, at the same time, carried away by the creative forces driving all aspects of Jewish culture.</p>

<p>Despite increasing assimilation among the Jewish intelligentsia — which older Yiddish writers, like Z. Segalowitch, deplored; Segalowitch waged a war against what he called the <em>shmendrikes</em> (wise guys) who were becoming estranged from their own culture — the young Shneiderman saw great opportunities for himself as a Yiddish writer. His energy and ambition were virtually inexhaustible. He tried every literary genre: he wrote poems, published interviews with Polish writers in <em>Literarische Bletter </em>, translated Polish poems and novels into Yiddish, and wrote songs for the Yiddish theatre. Years later, this is how Melech Ravitz, in his book <em>Mein Leksikon (My Lexicon)</em>, good-humoredly characterized this early period in Shneiderman’s career:</p>

<p>“Shneiderman brought poems with him from Kuzmir, many poems, a good knowledge of Polish, and a readiness to undertake every kind of literary endeavor: an article, a review, a translation, a poem, a short story, a news report…I once even wrote a little lampoon against him when he was a novice poet and journalist and the piece was a big hit among his fellow writers. From this, I deduce that in the literary community you don’t have to wait for a Nobel Prize or world fame to find rivals. You can have them right at the first rung of your career.</p>

<p>Because of my attack, Shneiderman became three times as energetic and he attacked me on three fronts. First, he sent me some poems under a pseudonym; he fooled me and I gave the poems a good review. Second, he attacked me in print. Third, he submitted the case to the judgment of our fellow writers…Needless to say, we were soon reconciled and even became great friends.”</p>

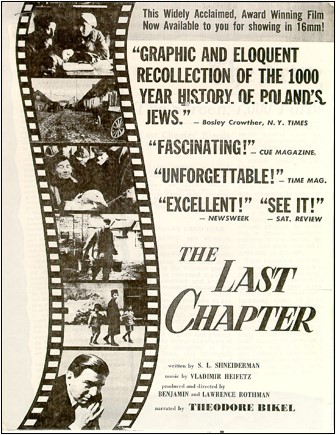

<p>In those first few years in Warsaw, besides exploring a variety of literary genres, Shneiderman also became interested in the new art of the cinema.</p>

<p>In September 1928, the first Yiddish journal devoted to the cinema, <em>Film Velt (Film World)</em>, appeared in Warsaw. The journal was edited by Saul Goskin and Mark Tannenbaum and the two most important articles in this first issue were by Shneiderman. We were reminded of all this by Jim Hoberman, author of the great work (in English) on the history of Yiddish film, <em>Bridge of Light: Yiddish Films Between Two Worlds</em>. This richly illustrated, 400-page book was published in New York in 1991 by the Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with Schocken Books. The museum organized a large exhibit on Yiddish films (we attended the opening of the exhibit) and for six months showed a Yiddish film every week. The film festival was made possible by the National Center for Yiddish Film at Brandeis University in Boston, which collected the old films and restored many of them.</p>

<p>Hoberman brought our early years back to us when he sent us a copy of the first issue of <em>Film Velt</em> from 1928, which contains Shneiderman’s two articles. One of the articles, “Film Has Deep Meaning,” is signed by S. L. Shneiderman, and in it he argues that the new art of movie making is an important form of cultural entertainment for the masses. He emphasizes the social significance of the cinema: international, it brings together citizens from every land, opposes war, and appeals to a wide audience.</p>

<p>The second essay, “Behind the Scenes of <em>In the Polish Woods,</em>” recounts the excitement of making a film based on the novel by Yosef Opatoshu, which had aroused a great deal of interest. The movie, a monumental work, was produced by Leo Forbert, who was already well-known, and directed by Jonas Turkow; the screenplay was written by H. Bojm. Forbert and Bojm already had two popular Yiddish films to their credit: <em>Tkies-Kaf (The Agreement)</em> and <em>Lamed-Vovnik (The Hidden Saint)</em>.</p>

<p>Fascinated by the broad historical scope of the film, Shneiderman followed its production very closely. He once took me along to the set to watch the film being made. The outdoor scenes were filmed in the region around Piaseczno, a shtetl near Warsaw, where, incidentally, my uncle, Mendel Segal, who was the scribe (secretary) for the Jewish community, lived. The scenes were shot in a beautiful part of a dense forest, near a lake. The trip was a romantic adventure for us and Shneiderman’s enthusiasm was boundless.</p>

<p>Unfortunately, the whole enterprise, in which Polish filmmakers were also involved, came to a disappointing end. Because of protests from both Jewish religious quarters and Polish government authorities, some scenes were cut and the film soon disappeared from the screen. But the film quickly gained full recognition in America.</p>

<p>The article on <em>In the Polish Woods</em> was printed under Shneiderman’s pseudonym, “Emil.” He was known by that name among his colleagues, especially in Yiddish theatre, and that is what my family called him. In his own family and in Kuzmir at large, he was still known by his real name, Shmuel-Leib.</p>

<p>The journal <em>Film Velt</em> appeared for ten months, from September, 1928, until the summer of 1929. It may have been the only one of its kind in the entire history of the Yiddish press.</p>

<p>In Israel, in 1988, at a conference on the history of the Jews in Poland held in Jerusalem, Shneiderman had another encounter that also reminded him of his early years in Warsaw. Among the scholars present at the conference was the Polish art historian, Prof. Jerzy Malinowski, who had just finished a book on the Yiddish avant-garde movement centered on the journal, <em>Yung Yiddish (Young Yiddish)</em>, published in Lodz from 1918-1925. Researching the history of Polish art after World War I, Prof. Malinowski came upon many poets and artists with Jewish names. That led him to <em>Yung Yiddish</em> because, despite denunciations from the antisemitic press, many of the Polish avant-garde artists participated in the Jewish movement’s exhibitions and literary gatherings.</p>

<p>In the first of a series of essays on Prof. Malinowski’s book, Shneiderman wrote:</p>

<p>“I was deeply moved by the book about <em>Yung Yiddish</em> and, unnerved, I devoured page after page…all of a sudden the writers and artists murdered in Hitler’s death camps and in the ghettoes at Lodz and Warsaw rose up alive before me. Only a few, like Moshe Broderson and the painter Yankl Adler, survived the Holocaust, but they have since passed away.</p>

<p>That wonderful moment of my youth came back to me in all its colors, the moment when I first arrived in Lodz and Warsaw and there came face-to-face with the poets and artists of <em>Yung Yiddish</em>. Along with his book, Prof. Malinowski gave me a photo of my portrait painted by Wolf Weintraub in 1925. Weintraub was then already a well-known artist and he had been a great friend to me during my ‘debut’ in Warsaw. This portrait (which, nonetheless, bears little resemblance to its subject) is reproduced in Prof. Malinowski’s monograph as an example of expressionism, of which Weintraub was one of the pioneers in Poland.”</p>

<p>Beneath the portrait is written: “W. Weintraub — Portrait of the young poet, S. L. Shneiderman.” Weintraub also designed the cover for Shneiderman’s first volume of poetry, <em>Gilderne Feigl</em>.</p>

<p>For many years, the futurist manifestoes of Moshe Broderson, styled after V. Mayakovsky, continued to resonate among Yiddish poets. This can be seen, for example, in the speech Shneiderman gave at the Congress for the Defense of Culture in Paris, in 1935. The speech (published in <em>Literarische Bletter</em>, July 19, 1935) begins as follows:</p>

<p>“The man addressing you today is a citizen of the Land of Yiddish, a land without barracks, without soldiers — a land in which a pen is the only weapon. You won’t find this land on any map, the boundaries of this land can be found only in the regions of cultural achievement and heroic artistic labor.</p>

<p>More than any other, Yiddish literature carries within itself the kernel of anti-Fascism…from the beginning, Yiddish literature has depicted the struggle against want and oppression.”</p>

<p>The generation of <em>Yung-Yiddish</em> was also buttressed by the Warsaw avant-garde journals: <em>Chalyastra</em>, edited by Peretz Markish, who spent five years in Poland before returning to Moscow; <em>Albatros</em>, edited by Uri-Zvi Greenberg. Melech Ravitz, I. J. Singer, and Uri-Zvi Greenberg also belonged to the <em>Chalyastra</em> group.</p>

<p>In his series of articles on <em>Yung-Yiddish</em>, Shneiderman also discussed the interest that this group of poets and painters aroused in America when the works of Yankl Adler, Mark Shwartz, Henrik Berlevy, Yitzhak Brauder, and others were shown in New York in the early 1920’s. Sholem Asch was the first to buy two paintings by Yankl Adler, who later enjoyed international fame. The poets of<em>Yung-Yiddish</em> formed a close alliance with the American group called the <em>Yunge</em> (Young Ones), especially Moshe-Leib Halpern, Zishe Landau, and Yosef Opatoshu.</p>

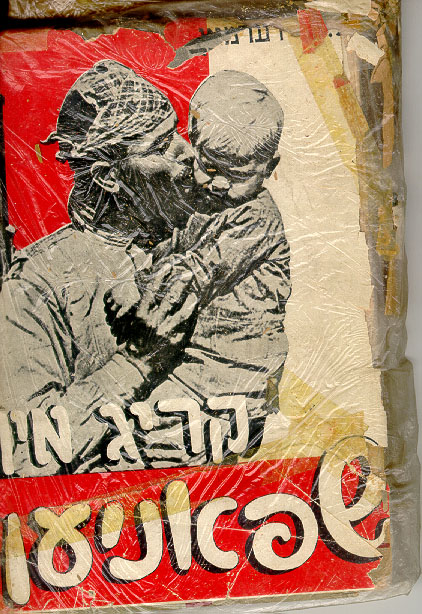

<p>We lived in Paris from 1933 to 1940. During that time, under the influence of the master of literary reportage, Egon Erwin Kisch, the young poet S. L. Shneiderman began to write prose. His reports from the Spanish Civil War were published by all the Yiddish newspapers, by<em> Ma’ariv</em>in Israel, and by four Polish-Yiddish newspapers. A selection of these reports also appeared in book form along with photos taken by my brother, David Szymin (Chim), who was in Spain as a news photographer for French magazines. The book was published in Warsaw in 1938, by the well-known publishing house owned by my father, B. Szymin, while the war in Spain was still going on.</p>

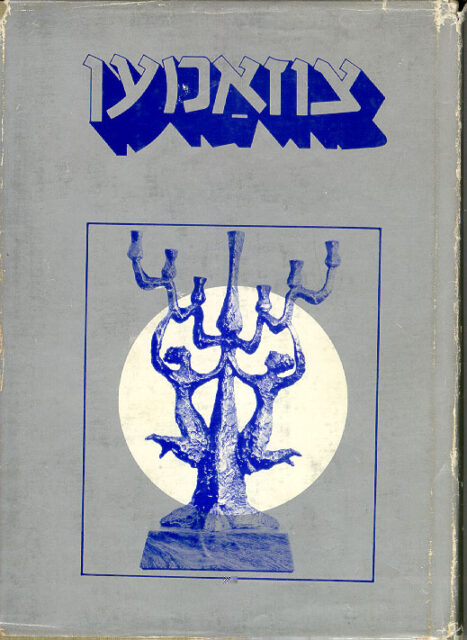

<p>Shneiderman’s first volume of reportages, <em>Zwishn Nalewkes un Eifel-Turm (Between Nalewky and the Eiffel Tower)</em>, appeared in 1935, with a foreword by E. E. Kisch. After the collapse of the Spanish Republic in 1938, Shneiderman was invited for a lecture tour in South Africa; on his way back, he visited Israel for the first time.</p>

<p>In my archives, I found a rare document concerning our departure from Paris in the early months of World War II: the February 9, 1940, issue of the short-lived weekly, <em>Die Voch(The Week)</em>. On the first page, there is a news item reporting that S. L. Shneiderman and B. Frimer have embarked for America on a mission for the Federation of Polish Jews. My hands trembled as I leafed through the four large sheets of yellow and crumbling newspaper which had been published by the Federation of Polish Jews in Paris together with the relief organization for Jewish refugees from Poland, where the Nazi occupation had already sown death and destruction in ghettoes and labor camps. Shneiderman and Schlomo Rosenberg were the editors of the weekly and Shneiderman, accompanied by Frimer — set off for America to raise money for their enterprise.</p>

<p>Those four sheets of newsprint record the tragic moments just before the Holocaust. The Jewish refugees who had managed to escape to Paris were literally barefoot and naked and in need of immediate material aid.</p>

<p>First to catch the eye on the front page are the four empty spaces stamped in French, <em>censur</em> (censored) — which shows how hard France was trying not to provoke Hitler’s Germany. On the same page there is also a long article by Dr. Heszel Klepfisz, “The Jews of Poland.” By then he was already a noted scholar of the history of Eastern European, or Ashkenazi, Jews and had written articles for Orthodox publications in Warsaw. After we left for America, Dr. Klepfisz became the editor of <em>Die Voch</em> and remained in that post until he was drafted into the army. In May, the Germans overran Paris.</p>

<p>This issue of <em>Die Voch</em> also contains a heartrending report by Z. Segalowitch, who had just arrived in Paris from Poland. He tells how, when war broke out, in confusion the Jews from the shtetls tried to flee to Warsaw and from Warsaw to the Soviet or Rumanian border. Thronging the roads, the Jews were bombed by German planes and many were killed.</p>

<p>A poem by A. Leyeles, “Lament of the Fields,” is printed in this newspaper and also a letter from Israel by M. Wolman-Sieraczkowa about a Jewish-Arab “peace conference,” which is supposed to demonstrate that relations between Jews and Arabs are improving… An article by M. Dluznowski about the Federation of Polish Jews in Paris and New York. And next to it — an enthusiastic review by the art critic, H. Aronson, of a showing of some works by Marc Chagall. Even in the announcements and advertisements, many of them censored, one can feel terror at the approaching disaster. And how ominous an article such as “Let Us Organize,” (A. Rosen) or “What Is <u>Really</u> Going to Happen to Us Jews?” (H. Hochbaum) sounds to us today.</p>

<p>I am dwelling on this newspaper not only because it touches on our biography, but also because this may be the only extant copy of that short-lived publication and because it is a relic of that tragic moment when the extermination of the European Jews had begun.</p>

<p>Arriving in New York after a six-day journey aboard the liner <em>Manhattan</em> and after another week in Ellis Island, we somberly began the process of settling in the new land. Anxiety about the fate of our friends and relatives in Poland and about Shneiderman’s brother and sister in Paris still plagued us in the free land of America.</p>

<p>We lived in America for nearly fifty years, but we frequently traveled to Israel, France, Poland, and other countries in Eastern Europe. In his reports and essays, Shneiderman described the conditions in the dwindling Jewish communities and what they had experienced during the Holocaust.</p>

<p>* * *</p>

<p>As our archives in New York grew larger and larger, it became necessary to find for an appropriate and permanent place to house our collection of printed works and manuscripts, letters, and unfinished works, along with the rich collection of source materials in many languages. We chose the Institute for Diaspora Research at Tel Aviv University. The head archivist at the Institute, Prof. Joel Raba, gratefully accepted our offer and since 1988, with the help of the Friends of Tel Aviv University in New York, we have been sending him crates of documents, more or less organized.</p>

<p>I decided to talk about “my” archive some time ago, after a Kol Israel broadcast, in Yiddish, transmitted a rather long interview between Adam Grusman and the writer Yosl Birstein, who had just finished cataloging the archives of Melech Ravitz stored in the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. According to Yosl Birstein, it took a full twenty years to prepare the catalog. This, however, does not deter me from what I still intend to accomplish so as to leave my husband’s legacy in better order for the archivists who will catalog it.</p>

<p>And perhaps there will come a young scholar whom these archives will help to understand our epoch, full of grand intellectual achievements and horrible destruction, as it is reflected in the works of this extraordinary writer — a poet and, as M. Tsanin called him, the first modern journalist in Yiddish literature — S. L. Shneiderman.</p>

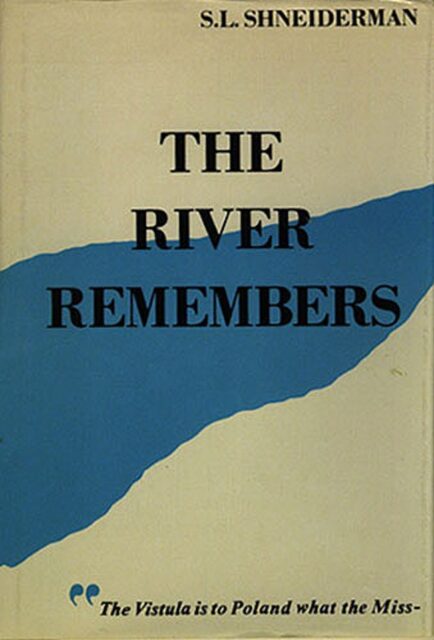

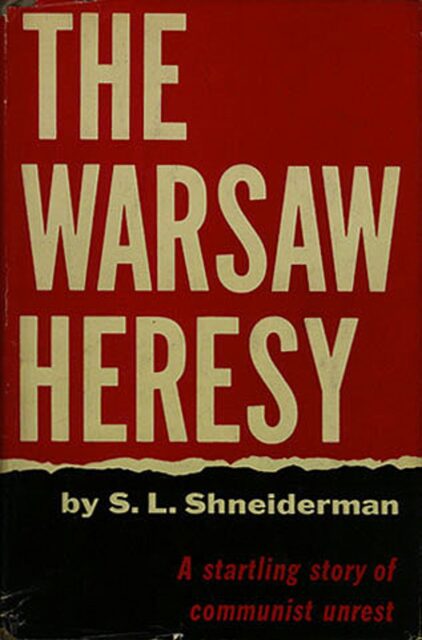

<p>Searching through my archives to make a selection of his works for this book, I felt like a deep-sea diver hunting for treasures at the bottom of the ocean… So I decided, first of all, to include chapters from each of his four books, and as part of my introductory chapter, digests of some of his long series of reportages which appeared in newspapers in installments but not in book form. Because of the declining market for Yiddish literature, Shneiderman’s books are now unlikely to be reprinted, so at least these “samples” will appear in a new edition. The reader will also find a fairly substantial chapter containing Shneiderman’s reminiscences, “Notes for an Autobiography,” a selection of his poems, and critical essays on writers to whom he was particularly close.</p>

<p>The articles about Shneiderman are critical essays by leading Yiddish writers and journalists and as such, enrich the contents of this book. I am grateful for permission to reprint these essays.</p>

<p>In conclusion, I must add that without the help and encouragement of my daughter, Helen, her husband, Haim Sarid, and my son, Ben Shneiderman, and without the love and interest of my five grandchildren, I would not have been able to complete this difficult undertaking.</p>

<p>I owe special thanks to Shlomo Shweitzer, writer, editor of the I. L. Peretz Publishing House, and old family friend, for his deep interest in this book, which was published by the Peretz Publishing House in Tel-Aviv.</p>

<p>I would also like to thank the writer Zvi Hirsh Smolyakov who prepared the proofs for this book and helped me select the works included here.</p>